At the beginning of the 20th century the new generation architects had enough of the

eclecticism - the copying of older styles - and were eagerly searching for what

they called "a modern style".

Despite the flourishing Jugend (Art Nouveau) style on the European continent that

partly affected the Swedish architects, the new generation of Swedish architects

wanted to create a style of their own as they saw the Jugend style too international

for their taste. Similar to the Jugend architects, they were looking for old

handicraftship but with a genuine national style, influenced by the buildings from

the renassaince period of the 16th century. The result of their achievements became

what we today call "Swedish national romantic architecture", which had its era of

prosperity around 1910.

I will now explain the story behind the style.

Sweden and the national matters

At the end of the 19th century, the hopeful period of internationalism and free trade

was replaced by period of increased protectionism, i.e. protection of the own country's

production against foreign competition. The European countries closed themselves within

their own borders. The great powers formed alliances to strengthen their positions.

At one side there was the old great power England, and on the other side the new great

power Germany. It was now only the igniting spark that was lacking to make the first

world war a fact.

In Sweden, the emigration to the United States undermined the national self-esteem.

This and the growing foreign competition, caused the Swedish farmers to lead the way

to carry through duties on foreign merchandises with the slogan "Sweden to the Swedish".

Even though they were in minority they managed to force through their demands.

Perhaps the most important matter that caused the heaviest emotional storm was the

relationship to the neighbour countries. In connection with the loss of Finnland in

the 1809 war, Norway was conquered. The Norwegians saw themselves more and more as an

independent nation and simply withdraw the union with Sweden in 1905. In Finnland, the

old Swedish cultural values were downtrodded by the Russian aggression. The Russian

occupation of Finnland made the Swedes impatient and anxious about the defensive

preparedness behind the Swedish borders.

Art and architecture were affected by the political events and had a major importance

to the people. It was therefore obvious and natural to visualize their national feelings

in their works. In contrast to their colleagues in the eastern neighbour countries,

they didn't uphold any supremacy, rather to concentrate on deep-lying national

characteristics, the innermost essence of the Swedish people and the secrets of nature,

as Bertil Palm, biographer of the architect Carl Westman, wrote:

In the Swedish nature poetry of Fröding and in the tunes of Värmland

the genuine Swedish distinctive character appeared to him in roguish jocularity and

brooding melancholy. There wasn't any nationalism, no holding up of the patriotism,

the Swedish tone rang originally pure and without a lot of fuss.

The dilemma of the 19th century

The style eclecticism, the reactionary architecture, of the 19th century meant for some people a feeling of security, while it for others meant a checking band. The established architects of the time adapted their style to the purpose of the building. Theatres where carried out in swelling baroque, the dwelling houses of the authorities in tight classicism and churches in the benit for the gothic of the Middle Ages. A chaotic architecture which corresponds to a chaotic society. The appearance of a new upperclass of hard working businessmen made the eclecticism even more apparent, as the Finnish art historian and architect Gustaf Strengell put it in 1901:

The upstarter, the coin matador, accomodates his house with princely luxury and furnishes his dining room in German renaissance and his budoir in rococo, as his grandfather had been a count at Rhen and his great-grandfather had been dancing in satin shoes at the balls in one of the many duodez-Versaille's of the 18th century.

At the academies of arts, the values of art where definite, and the climax had already been reached in the classical antiquity, the gothic, the renaissance, baroque etc. Around 1890 the opinion of art changed to be relative, meaning that all art must be looked at according to the relationship to its time. The new generation of architects began the search for the characteristics of their time and to transform these into architectural forms. The new ideas where often supported by the far-sighted representatives of the new upper class as they didn't feel satisfied by the attempts of copying and outshining the manner of living and language of form of the nobility.

Historical retrospection

While architects in the 19th century searched in history for a choice of style, the national romantics searched more freely for details and characteristic features of specific works in the national history. They tried to combine these features into a new unity.

Inspired by the Arts & Crafts movement the Swedish architects got impulses to the old brick layering art that now became common in England. It represented values that one wanted to protect - the simple life, the skills of craftsmanship and the working organization. These where values that they meant were impoverished because of the industrialization. The legends and natural mysticism of the Middle Ages probably also had an attraction on the romantic coloured artists.

Carl Curman's Old Norse

inspiring summer house (1880), Lysekil

Swedish architects collected fuel from both the everyday folk culture and the powerful magnificent palace and castle architecture from the ages of the Swedish king Gustav Vasa (16th century). In addition, there were also elements of baroque and Old Norse motifs.

Vadstena slott (1545)

Two young Swedish architect students, Carl Westman and Ragnar Östberg, became typical representatives of the search for a modern architecture with connections to traditional Swedish architecture. These fellow students made trips to USA, Italy and Greece in order to study possible new elements in a modern architecture. They did, however, point out that their overseas studies where unnecessary the day they studied the older Swedish buildings in the country, the traditional red cabins and the 16th century castles from the kingdom of Gustav Vasa.

Östberg wrote:

It has been told about Gustav Vasa, that 'wherever he went, things grew up after him'. The time came when this growth moderated and got beaten, but the sprouts were too strong, too Swedish to die, no matter how little we payed attention to it and no matter how little our eyes saw.

With a strange movement, this growth forced upon me in the presence of the Vadstena castle, where I, remarkably enough quite late, for the first time saw this wonderful trace of the growth of Vasa. It was, like the great land builder suddenly stood in front of me, mighty and sound, with a grip that felt, with a grip that turned and prised and put everything in order and with a wisdom told me: 'everything will be alright'.

So natural that our Vasa-father and his sons would form this renaissance of the Swedish architecture, sound and fluent like the sap! As natural as it was decades ago for the powerful families of Rome and Florence to build up the style that sang about their greatness.

Many of the great buildings by the national romantics show that old buildings served as a source of inspiration. Carl Westman's town hall has strong traits from Vadstena castle, Ragnar Östberg borrowed the backyard interior from Läckö castle to the city hall, Torben Brut had the complete town wall of Visby, "our lifelike medieval town", as a prototype to Stockholm Stadium, host of the Olympic Games of 1912.

Back to nature

At the end of the 19th century, people in the industrialized areas experienced a life distinguished by more stress, more pollution and harder living conditions. People started to appreciate the natural surroundings. Some people chose to live in the suburbs and commuted to work by train.

Bruno Liljefors: 'Vårnatt' (1896)

The longing for nature wasn't only a longing to be able to live a strengthening outdoor life, coloured by hygienic aspects and soundness ideals. It was also a longing for something natural and primitive, something that was yet untouched by the industrial civilization. The life in the city was experienced by many as artificial, an existence that was opposed to the nature and essence of man. Carl Westman meant that the direct natural science was the only way to show a way out of the style eclicticism and to return a sound creative joy.

Richard Bergh: 'Nordisk sommarkväll' (1900)

Inspired by the Arts & Craft movement, he wanted to...

...compose the architecture with respect to nature and to complete the nature with respect to the building, so as thay seem grown together...

Even though these ambitions where complicated to realize in a city environment, the church Masthugget in Göteborg is a good example. Great granit blocks in huge walls form the crossing between the natural hill and the darkred brick walls so as the whole church seems grown up directly from the rock.

Masthuggskyrkan, Göteborg (1915)

The spirit of nature makes everything merge into an undefined entirety - man becomes a part of nature and nature inspires and gets human characteristics. Myths and fairy tales became important sources of inspiration. In the fairy tale illustrations of John Bauer, we meet e.g. the forest and its beings. His paintings are filled with mysticism, sometimes sympathy, sometimes melancholy. The buildings seem to be more than just a shell for a certain activity, they was a kind of unique being that could mediate moods and feelings The influence of nature also affected the architect, who chose working with, what they called, "living materials". Lars Israel Wahlman wrote in 1908:

The pines are individuals, full of wind and song, of crossing and storm, of character and purposeful aspiration. They are more venerable than ourselves. Timber are trees, which life has become a fairy tale. To build walls of them, is to close yourself indoors with your conscience between antiquity and future.

John Bauer: Prinsessan Tuvstarr (1913)

The renaissance of the handicraft

As a result of the architect's attitude towards "living materials", the handicraft became an important part of the architectural style. Machine struck building bricks were regarded as boring, hand struck as vivifying. It wasn't, however, easy to find skilled craftsmen. The architect Ivar Tengbom tells in 1904:

Brickworks have - even reluctantly - been forced to search for old retired brick layers, who can bring back the brick layering from its forgetfulness.

Ornament

The Arts & Crafts movement had strong influences on the architects as they had the same opinion regarding handicraft made versus industrial manufactured products, as William Morris put it:

...nothing ought to be made that doesn't give joy to both the manufacturer and the consumer...

It was the pleasure in one's handicraft, in the manual work, that was the source of the art, and preferably the craftsman and the artist should be one and the same - the artscraftsman, something he tried to achieve in his own workshop.

The strive for the genuineness and truth was the foundation stone of the use of "living materials". One architect of importance in this view is Isak Gustaf Clason who wrote in 1896:

One has established, besides the before alone worshipped beautiful, two other gods - the right and the good. Which in the architecture means that no beauty can be achieved except by truth in construction and goodness in the design.

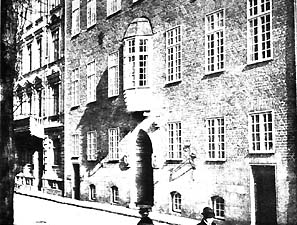

Carl Westman: Läkaresällskapets hus (1906), Stockholm

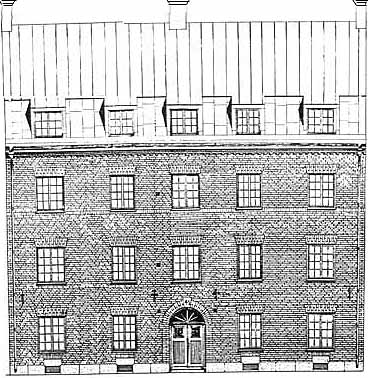

Ragnar östberg: Rådhuset (1915), Stockholm

Characteristics of a large house

Characteristics of a small house

The end of the national romantic epoque

The rampaging of the industrialization was of course the all-pervading phenomenon

during the 19th century. The architects where generally not involved in the development

of new materials and manufacturing processes. Instead, the engineers replaced the

architects when building new factories and other "non-architectural" tasks.

Without major aesthetical ambitions, the art of the engineers was developed to

masterpieces like the the Crystal Palace in London, 1851, and the Eiffel Tower in

Paris, 1889. The gap between the architects and the engineers was especially clear

when building railway stations. The engineers often provided the railway yard

with venturous wide roofs in iron and glass, while the artchitects chose a faithful

style historic front. This difference didn't cease with the national romantics,

as they honoured the old traditional building technique and handicraft.

They reacted against the blooming industrialization, its soulless and uniform

products, and the negative consequences to the society.

By their negative attitude towards the industrialization the national romanticism

became however a movement that in some respects worked against the developments of

time. They didn't see the great possibilities that now in fact was open to them.

However, they couldn't completely turn their back upon the industries. For example

they couldn't in the long run say no to neither the bathroom nor the elevator,

despite that both of these increasing conveniences was the grateful result of the

progress of the industrial production. A substantial problem was therefore to decide

where the delimitation should be, how much of industrial production they could

accept without any loss of the artistic values and the impression of a handicraft

built house. At the same time, they couldn't bring themselves to reach out their

handicraft products to the large public. When being short of money, the choice was

easy between the expensive handicraft and the cheap industrial manufacture, so

despite the ambitions of "beauty to all" the national romanticism therefore became

a phenomenon for the elites.

Around 1915, the criticism was addressed to the national romantics themselves.

The ones who now belonged to the younger generation thought that an up-to-date

architecture couldn't be accomplished without the use of the new technology.

Without this starting point, also the national romantic architecture in some degree

became to stand out as pastiches. The artist Isaac Grünevald meant in 1913 that the

modern architect's task really ought to be to work with the new instruments that

the art of the engineers had put in their hands:

"But the Swedish architect puts an engine in a gold chariot. The

existing Swedish architecture is nothing but enlarged old country houses and medieval

castles. The architect drops the roofing tile in mass of mud or soils it in other ways,

processes copper roof with acids to make it look like past times, plaster the wall so

thin that the building bricks shine through and on some areas look completely collapsed,

build the bricks uneven as they where made with the tools of the prehistoric age,

makes metre thick walls as to endure a medieval siege and despite the development

of the glass industrial manufacture he persistently answer for the little leaded panes."

Gregor Paulsson agreed with the criticism in the book "The new architecture" from 1916.

One had to accept the production methods that existed, and look for support in the

society's driving forces - the industry and the commerce, not to turn away from them.

Besides, the machine itself wasn't a threat to the beauty, as Morris and the national

romantics stated. Therefore it was a matter of gaining the mastery of the machines,

turn them to obedient tools and to not being afraid of them. Paulsson also made an

assault upon other principles of the national romanticism. He meant that the particular

characteristics of the time - the individualism - was unjustifiable, and that it was

impossible to, for example, further thinking of every house in one copy only when many

great building tasks where in front of them. Mass production would become necessary,

and the artist and the architect would step down from the high horses and place oneself

in line as "the best, among equals". The production would direct towards the large

public instead of separate individuals. The architects also should take less interest

in the matters of style and more interest in the current problems and possibilities of

the time. Then a new language form would grow and one should no longer need to ogle at

past times to find ideals. Paulsson also made an attempt to look forward and describe

the coming tasks and with what means they should be approached:

"The renaissance in Scandinavia was of the decorative form of art, we

want to achieve the function... We have, to put it plainly, huge tasks to wrestle with.

We have houses larger than the little castles of Gustav Vasa, we have factories,

public buildings of a new kind, we have brand new building materials, iron and concrete.

The elasticity of the iron, the springy strength and power of the concrete to join at

our most bold desire give the building a brand new skeleton. We have new conditions -

and new possibilities. The concrete and the girders make the straight cubes and the

magnificent vaults, against which the cathedrals of the Middle-Age ought to come to

nothing.

The development towards "the straight cubes" perhaps didn't become a reality as soon

as Paulsson imagined, the architects where not ready to abandon history for yet

some time. Between the national romantic architecture and the break-through of the

functionalism a period of classicism first appeared.

An important source of this article is the working of an essay in the course

Theory and History of the Architecture: "Svensk Arkitektur 1900-1930"

by Ulla Antonsson and Stefan Lundin, Chalmers, Göteborg, 1981.

Partly reprinted and translated with their kind permission.